Singing and Vocal Teaching

After a successful singing career with English National Opera, Richard left the company in 2007 with a mission to pass on to others the benefit of his experience. He had joined the company as a member of their critically acclaimed chorus, as the youngest male singer in the company at that time. As he developed with the company, he sang and understudied many supporting roles with them, as well as major principal roles with smaller companies, including Chiltern Opera, Opera Omnibus (now Opera South) and Holland Park Festival. He had originally trained as a baritone, but quickly moved up to sing as a tenor, flourishing in high lyrical roles such as Tonio in 'La Fille du Regiment', Elvino in 'La Sonnambula and Rodolfo in 'La Boheme' during the early part of his singing career. He went on to sing Pinkerton, Turiddu and 'Don Jose', also adding several leading Verdi roles to his repertoire. In more recent years the voice grew and deepened to encompass much of the Wagnerian repertoire, most notably Siegmund in 'Valkyrie'. This is a highly specialised repertoire and conflicts somewhat with the particular demands of professional chorus work, so he has taken an indefinite break from work as a performing singer, in order to pursue other facets of his wide ranging musical resource.

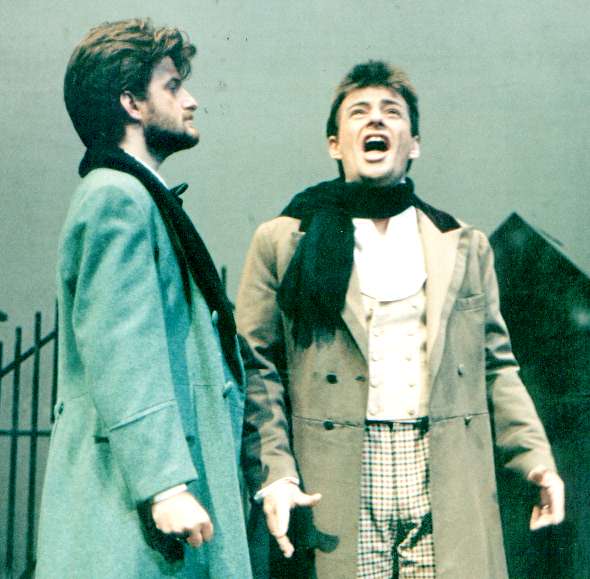

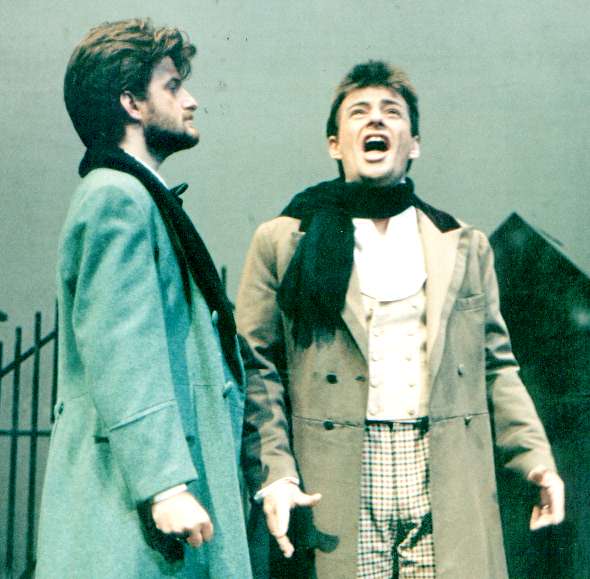

A very young Richard Cartmale as Rodolfo

in New Decade Opera's 1987 production of La Boheme

The Marcello is Ian Bloomfield.

Operatic

roles and understudies for ENO

1988-2007

(a

representative selection)

Wulfram (“TheTales of Hoffmann”), Varro (Stephen Oliver’s “Timon of Athens” ), Flute (“A Midsummer Night's Dream” ), Trabucco (“Forza Del Destino”), The Cock (“The Cunning Little Vixen”), The Coachman (“Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk”), Animal Seller, Act2 Major Domo and 1st Waiter (“Der Rosenkavalier”), Giuseppe (“LaTraviata”), 2nd Jew (“Salome”), Kuzka (“Khovanschina”), Soldier (“Wozzeck”), 2nd Knight (“Lohengrin”), 1st Knight (“Parsifal”), Peasant Leader (“Eugene Onegin”). 1st Tenor solo – act II (Turnage’s “The Silver Tassie”- World Premiere 2000)

Major Operatic solo work

(excluding ENO)

1986 - 2007

Rodolfo

(La Boheme), Elvino (La Sonnambula), Tonio (La Fille du

Regiment), Edgardo (Lucia di Lammermoor) Pinkerton (Madam

Butterfly) Turiddu (Cavalleria

Rusticana), Don Jose (Carmen),

Duca di Mantova (Rigoletto), Gustavus III (Un Ballo in Maschera) Siegmund (Valkyrie) {concert performance with Essex Symphony Orchestra.}

To hear a short section of a live recording of Richard Cartmale singing

Siegmund in Wagner's 'Valkyrie' go to here (broadband required)

Richard Cartmale writes on Vocal Technique (with particular emphasis on the treatment of young voices)

. The warning signs are typically most evident in the 'stars' of a school's music department, particularly 15-19 year old girls who are outstandingly accomplished musicians in general and sing soprano in the School's main and Chamber Choirs, as well as singing solos and playing several instruments. Such 'golden girls' may well aspire to be choral scholars. Often they succeed, but by the time they reach University they could be doing an as much choral singing as a professional opera chorister on a job-share. More to the point, they would be doing this too young and on a defective technique. Fine - if they don't ever want to sing again after the age of 30-they might even be lucky, but if they want to be real singers they will (sooner rather than later) start to make more visceral and emotional artistic demands on their voices, particularly if they start singing opera or dramatic cantata recitative.

As both conductor and singer, I understand the lure of serving the music at the expense of the singer, but the young inevitably feel themselves to be indestructable, and will not be truly attuned to conflicts of interest between musical goals and vocal longevity. As a conductor or coach of adult professionals (or amateurs with the luxury of long recovery times) one might be forgiven for demanding this sacrifice to the greater good, but it is unforgiveable where children are concerned

There is a truism that the better a musician someone is, the harder it is to train their voice. I would contend that it is more specifically a case of: the more deeply somebody feels and wishes to serve the music (and the drama-even of a concert piece) then the more difficult it is to train their voice. Notice that I say difficult - not impossible. There are many differing ideas of a 'good musician' - just among singers. Some people earn the accolade by being good sight readers and being blessed with a fairly light and flexible instrument. What such singers may also have is a splendid detachment from what they are singing. This is undoubtedly useful, because a cool head for the mechanics of vocal performance is needed to ensure a consistently professional result . The trouble is that, in the end, an audience would secretly prefer to be thrilled and involved by a singer's performance, rather than just nodding because there was nothing obviously 'wrong' with it. As with any instrument, the greatest artists take risks - they 'push the envelope'. Inevitably Maria Callas springs to mind. No one could ever have accused her of being a mediocrity, with a nice voice, doing just the bare minimum required of her. Sadly such singers and such players ( Think of a pianist like Martha Argerich) are in short supply. They always have been, but it would be reassuring to feel that the next generation of such wildly human talent would be recognised for what it might become, and trained with a sufficiently robust technical grounding not to be broken on the wheel of their own artistic ambitions!

I feel a strong mission to bring these insights to musical theatre performers as well as to classical musicians. Of course being a conductor as well, means that this knowledge is also fed into all of my work with singers as a component of the musical preparation. Nothing beats a classical education! Ask any dancer in commercial theatre who trained in ballet. Ask any actor with a background in Shakespeare.

Sooner or later the work one does in the commercial or popular sector of the industry will cry out for that backstory of cultural depth and training pedigree. If it is not there, then an opportunity to do something wonderful, subtle, powerful and beautiful will have been squandered.

Is that so very bad? Actually I think it is!

Considering what a competitive industry this is, there is no excuse for mediocrity. Explanations may abound, but I say again-there is no excuse.

I think one explanations is that there are so few outstanding voice teachers, even for the future principal singers of our opera houses. How can we reasonably expect these busy experts to find the time to work in our Drama schools as well, even if they understand the repertoire and specific vocal adaptations of music theatre? Another explanation is the assumption deep in our national musical culture that a competant keyboard musician ( be it an accompanist or a church organist) can actually teach someone the physical processes of singing. Outstandingly musical boys with a pleasing natural voice are sent to cathedral organists, who at best will train them to sound like a choirboy (well they would, wouldn't they?) which militates against any other more widely musical application of the voice (even before it breaks) These boys are surrounded by professional adult male role-models who (usually, but not invariably) specialise in the same performance tradition - where sounding too much like 'men' would be frowned upon! Small wonder that so few young men take up singing lessons. Actors who wish to sing will often make their first port of call an accompanist or MD. Not a bad idea if that person refers them wisely, but what if they don't? All they will learn is the notes - not how to sing them. By the time this model has been diffused down to the level of the recreational theatre school, we encounter group 'singing lessons' taken not by a trained singer, but by a pianist, or even by an enthusiastic entrepreneur who has bought a backing CD and a franchise! None of these things are intrinsically bad, in so far as people develop an experience of making music, but to misrepresent them implicitly or explicitly as making a 'singer' of somebody is both ignorant and fraudulent.

You may also be interested to read my article 'What is a Coach?' which explores the important differences between a technical singing teacher and somebody who teaches you to apply your vocal skills to the music performed.

.........................................................................

One of my teachers was Richard Alda, who trained with the seminal vocal pedagogue, E. Herbert Cesare, but applied this knowledge to music theatre artists as well as opera singers. In the 1990s Alda taught four successive Jean-Valjeans for the West End production of Les Miserables. Having studied the writings of Cesare since the early 1980s when I first became interested in the sung voice, I naturally siezed on the opportunity to work with a pupil of the great man, and still use much of what he taught to this day. Other important influences have included two great British singers of the Wagnerian repertoire, both of whom I studied with earlier in my career - Josephine Veasey and Norman Bailey.

Return to Homepage:

Richard Cartmale, Conductor, Coach and Vocal Consultant